Examining the influence of Hollywood fiction on attitudes towards transgender people in an experiment using priming videos.

Introduction

It is estimated that around 0.5% of the adult UK population identifies as transgender (Government Equalities Committee, 2018). Unlike cisgender people, transgender identity does not match the gender they were assigned at birth. Reitz (2017) argued that many people will never get to know a transgender person in their lives, but, they will be exposed to transgender storylines on television and movies. The representation of trans characters in Hollywood fiction was not always the kindest; from 1960s to early 2000s, transgender characters in Hollywood films and TV shows were mostly presented as killers, villains or predators, often targeting (cisgender) women as their victims (de Castro, 2017). Subsequently, a new trope emerged from the 1990s onwards, in which transgender women and their bodies were mocked and viewed as disgusting. Furthermore, GLAAD (2012; formerly known as Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, now exclusively called GLAAD) found that from 102 episodes of U.S. TV series focusing on transgender storylines, only 12% of the episodes portrayed trans characters positively and 54% episodes portrayed them negatively, with the majority of characters being either victims of violent crimes or villains. Although the representation of transgender characters in TV shows became more positive and realistic with shows such as Pose (Koch-Rein, Haschemi Yekani & Verlinden, 2020), trans characters remain heavily underrepresented, particularly in popular Hollywood fiction.

Influence of Hollywood media on policy and prejudice

It could be argued that films and TV series are simply entertainment media. However, Neff (2015) proposed a concept of the Jaws Effect, where narratives from films were used as political devices to create real-life change, policies or laws perpetuating prejudice. Neff (2015) based this concept on politicians using narratives from the Hollywood film Jaws , which portrayed sharks as aggressive killing-machines, to pass policies allowing the catching and killing of sharks, resulting in a dramatic decline of many shark species. Politicians favoured harmful narratives instead of scientific evidence or statistics, and this is also seen in the passing of the House Bill 2 (HB2), which required people to use the public bathroom that matched the sex stated on their birth certificate (Reitz, 2017). Some politicians argued that this bill would protect women from predators wanting to assault them (Barnett et al., 2018), which seemed to be based purely on fictional tropes from Hollywood, since there has never been a reported incident of a transgender person sexually assaulting anyone in a public bathroom.

Transgender people's experience of victimisation

Furthermore, transgender people are more likely to experience sexual abuse than cisgender people; around 50% of transgender people have experienced sexual abuse at least once in their lifetime, with one in three perpetrators of the abuse being identified as intimate partners, and 90% of the survivors reported that at least one of their abusers was a cisgender man (FORGE [formerly known as For Ourselves: Reworking Gender Expression, now exclusively called FORGE], 2015). Moreover, some of the reported effects of the abuse included various psychological issues such as posttraumatic stress disorder, self-harm, attempted suicide, as well as physical issues such as long-term medical conditions and disability. Human Rights Campaign (HRC, 2021) reported that 57 transgender people were murdered in the U.S. in 2021 for simply being transgender, and these numbers are probably too low due to under-reporting. These statistics highlight the importance of conducting research which can contribute to the reduction of negative attitudes towards transgender people.

Existing research

There is a lack of literature on the influence of seeing negatively portrayed trans characters on viewer attitudes. However, Gillig et al. (2018) investigated the influence of viewing positively portrayed trans characters. The researchers recruited 488 U.S. viewers of the TV series Royal Pains , of whom 391 watched an episode with positive trans representation and 97 did not watch the episode. The study found that participants who were exposed to the transgender storyline reported significantly more positive attitudes towards transgender people (measured by Short Transphobia/Genderism scale) compared to participants who were not familiar with that storyline. Similar results were reported by Jones et al. (2018), who found that participants who were exposed to portrayals of trans people on television had more positive views towards them. However, there was no difference in attitudes based on what type of portrayal was viewed, and watching television more frequently correlated positively with attitudes towards transgender people.

When it comes to priming viewers’ attitudes, Taracuk and Koch (2021) used episodes from the TV series Star Trek (one with a positive transgender storyline and one without a trans portrayal) as an intervention to increase positive attitudes towards transgender people, measured by the Transgender Attitudes and Beliefs Scale. The researchers found a significant interaction effect between the type of media intervention (positive portrayal and no-portrayal/control) and the time of measurement (pre-intervention and post-intervention) on attitudes towards transgender people, where viewing a positive portrayal video of a transgender storyline increased positive attitudes towards transgender individuals. The research highlighted the beneficial influence of viewing positive transgender portrayals, but also emphasises the importance of conducting research on negative portrayals.

Aims and hypothesis

As presented above, at least 57 people were murdered in the USA in 2021 due to being Transgender (HRC, 2021). It is therefore essential for future attempts at harm reduction to understand how attitudes towards this population are being influenced. Previous research as summarised above has identified the priming effects of entire episodes of fictional representations of trans people, but either had possible confounds (participants had already watched the series involved, or were predisposed to watching more television) or did not consider the effects of a negative portrayal. The current study examines whether exposure to videos from Hollywood fiction portraying transgender characters really influences participant attitudes towards transgender people. Taking into consideration past literature, this study will observe if positive viewer attitudes increase after viewing a video positively portraying a trans storyline, and become more negative after viewing a negative portrayal. This is probably the first study to use a video negatively portraying a transgender storyline as well as short videos from Hollywood fiction, instead of full episodes, in order to prime participants. This is to determine whether viewing a transgender storyline of only a few minutes will be sufficient to change viewers’ attitudes. Based on the findings from past research and the present study’s aims, the following hypothesis was formed:

H: There is a significant interaction effect between the type of portrayal and the time of measurement on attitudes towards transgender people, where having viewed a positive portrayal video will result in the most positive attitudes, and having viewed a negative portrayal video will result in the most negative attitudes.

Methodology

Participants

Participants were recruited via snowball sampling; an anonymous link to the study was shared on social media, with a message encouraging people to share the link further. Snowball sampling (particularly through social media) was chosen, as it is a feasible sampling method allowing researchers to recruit a greater number of participants, who are not known or easily reachable by researchers (Leighton et al., 2021). The sampling method was different to that used by Taracuk and Koch (2021) to enable generalisation of the current study's findings beyond the student population. Some participants were also recruited in person by being approached at the University of West London (UWL) and at a local leisure centre. This was to avoid bias from recruiting only participants who are present on social media and diversify the type of recruited participants. Moreover, the study was posted on Sona Systems, which is a software that allowed Psychology students from UWL to gain credit points by completing the study. Overall, 200 participant responses were collected. However, 68 had to be excluded from the analysis; 48 due to being unfinished, three due to incompletion of questionnaires needed for the analysis, six due to not providing full consent, and eleven due to inadequate duration of study’s completion. That is, finishing the study in less than 6-8 minutes (depending on the type of video portrayal) meant that the participant did not watch the priming/control video, which was a crucial aspect of the study, so that their data could not be analysed. The final sample that was suitable for analysis consisted of 132 participant responses, with 43 participants being randomly assigned to the negative portrayal, 43 to the positive portrayal and 46 to the no-portrayal. The mean age of participants was 31.67 years old ( SD = 14.08), with minimum age of 18 and maximum of 80. As Table 1 below presents, the participants consisted of 59 cisgender women, 56 cisgender men, four transgender people and nine identifying outside the gender binary. The majority of participants identified as heterosexual (66.67%, N = 88) and had completed higher education (67.42%, N = 89). Moreover, 65 participants identified themselves as politically liberal and 41 as conservative. There were no notable differences between participants’ demographics for each of type of portrayal, and furthermore, all trans-binary participants and the majority of trans non-binary participants were randomly allocated to the no-portrayal condition.

| Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the participants (N = 132) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | N | % | |

| Gender identity |

Cisgender woman Transgender woman Cisgender man Transgender man Non-binary Genderqueer Genderfluid Agender Prefer not to say Would describe differently |

56 3 56 1 5 1 1 2 6 1 |

42.42 2.27 42.42 0.76 3.79 0.76 0.76 1.52 4.55 0.76 |

| Sexual orientation |

Straight (heterosexual) Lesbian Gay Bisexual Pansexual Queer Asexual Demisexual Questioning/unlabelled Prefer not to say Would describe differently |

88 3 7 11 2 5 2 2 2 7 3 |

66.67 2.27 5.30 8.33 1.52 3.79 1.52 1.52 1.52 5.30 2.27 |

| Level of education |

Left before Sixth form/collage Sixth form/collage Undergraduate Postgraduate Missing value |

14 28 63 26 1 |

10.60 21.21 47.73 19.70 0.76 |

| Political leaning |

Extremely liberal Liberal Slightly liberal Moderate or middle Slightly conservative Conservative Extremely conservative |

15 37 13 26 19 18 4 |

11.36 28.03 9.85 19.70 14.39 13.64 3.03 |

Materials

The feeling thermometer (FT): Participants were presented with five FTs prior to and after viewing some videos from Hollywood fiction. Only the FT assessing feelings towards transgender people was used for the analysis. The other four FTs (measuring feelings towards Brexit, feminism, legalisation of cannabis and the Black Lives Matter movement) were used as distractors to conceal the true purpose of the study (until participants were debriefed) in order to minimise any potential bias in participant responses. The rating of FTs started from 0, which represented very cold feelings/more negative attitudes, and ended on 100, which represented very warm feelings/more positive attitudes. The scales measuring attitudes towards transgender people used in previous research (Gillig et al., 2018; Taracuk & Koch, 2021) were not chosen for the current study, since asking participants questions regarding trans people would reveal the true meaning of the study to them before watching the priming videos and thus risk response bias. Moreover, the FT was used as a measure in the first identified publication exploring multiple various demographic variables as predictors of attitudes towards transgender people, in a population comprising no only students, which was conducted by Norton and Herek (2013). Based on the FT being used in previous research assessing attitudes towards trans people, as well as its ability to be disguised between other FTs (minimising potential response bias), it seemed the most fitting measure for the current study.

The priming and control videos: Three videos were used, positive and negative portrayal videos to prime participants, and a no-portrayal video for control purposes. The negative portrayal video consisted of scenes from a 1994 Hollywood film Ace Ventura: Pet Detective , which was chosen due to its mix of both Hollywood tropes: the transgender character was the villain of the film and her body/being attracted to her, made characters physically ill. Additionally, the film showed transphobic behaviours by the main character who ridiculed, humiliated, misgendered and exposed the body of the trans female character without her consent. The positive portrayal video was a mix of different scenes from a Hollywood TV series Pose , which was aired between 2019 and 2021. The scenes showcased a transgender female character who was becoming a motherly figure and displayed multiple positive qualities such as being caring and helpful. The trans character was also educating the cisgender character on experiencing life as a transgender person, and shared a story of being rejected for simply being transgender. The scenes were chosen to make participants feel sympathetic towards the trans character, to understand the experience of a transgender woman, and to see a trans character in a positive light. The no-portrayal video was a scene from a 1998 Hollywood film Babe: Pig in the City , which was used because it did not relate in any way to transgender people, LGBTQIA+ people, social change, politics, religion, or any other aspects that could influence participant attitudes and responses. The video mostly consisted of comedic and family-friendly interactions between different animals. The length of the video clips were as follows: the negative portrayal – 6.03 minutes, the positive portrayal – 5.23 minutes, the no-portrayal – 4.39 minutes. Short videos were used in the current study to minimise the risk that participants would become distracted or discouraged from watching the videos, and to determine whether short videos could be sufficient to influence participant attitudes.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the School Research Ethics Panel at the University of West London, based on the British Psychological Society’s Code of Ethics and Conduct. The study was then published through online survey host software – Qualtrics Survey Solutions. Before completing the study, participants were informed that it was “to examine the relationship between different variables measured by various questionnaires and viewers’ reactions to videos from Hollywood fiction”, in order to obscure the specific topic. They were also informed at this point that ‘Some of the videos that might be shown to you could include nudity, sexual references, inappropriate language, violence, and show discrimination or mistreatment’ and were given suggested helplines at this point. Once they had given consent, participants were asked to indicate their feelings towards transgender people and four other groups of people/issues (Brexit, feminism, legalisation of cannabis, Black Lives Matter movement) via feeling thermometers. Participants then completed scales measuring their level of religiosity, religious commitment and political leaning. The data from these three measures is not reported here, but was collected for a related study. Participants were then randomly assigned to either negative portrayal, positive portrayal, or no-portrayal, and were shown the Hollywood video which was appropriate to their condition. The videos were shared through the researcher’s Google drive, and participants could either watch them on Qualtrics or open the videos via Google drive. After watching the video, participants were asked to complete the same feeling thermometers as those at the beginning of the study. Subsequently, participants completed the demographic questions as reported in the participant section above, and received a debrief form, which revealed the true meaning of the study and reminded participants that they could withdraw their data from the study. Moreover, participants were provided with contact details to various mental health support organisations/helplines for the general public and for transgender individuals.

Results

The data collected from 132 participants via Qualtrics was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. The 3x2 mixed-design ANOVA was used to test the hypothesis, which referred to a significant interaction effect between the type of portrayal (positive, negative, or no-portrayal) and point in time of measurement (pre-video or post-video) on attitudes towards transgender people, where the positive portrayal video resulted in the most positive attitudes and the negative portrayal video in the most negative.

Mixed-design ANOVA assumptions

Prior to running the analysis, the assumptions for a mixed-design ANOVA were tested. Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for normality indicated that (after Bonferroni adjustments) the attitude data was not normally distributed in the no-portrayal condition ( Ds (46), ps < .001. However, there were no outliers (at two standard deviations above or below the mean), and Levene’s found no significant differences between the variance of each group’s data pre-video - F (2, 129) = .33, p > .05 or post video - F (2, 129) = .03, p > .05. Therefore, sufficient assumptions were met to treat the data as parametric and conduct the mixed ANOVA.

Participant attitudes towards transgender people and descriptive statistics

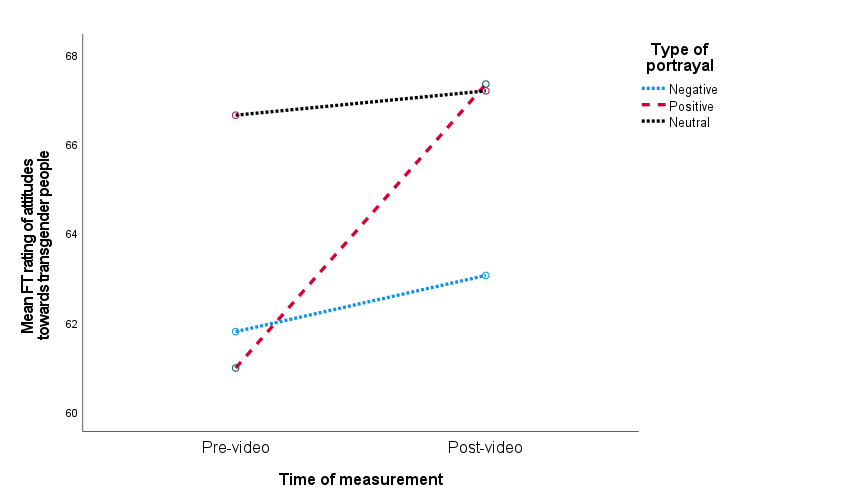

Figure 1 Line graph presenting the mean rating of the feeling thermometer measuring attitudes towards transgender people

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for participants’ pre-video and post-video feeling thermometer rating of attitudes towards transgender people in the negative, positive, and no-Portrayal types of portrayal

| Type of portrayal | Time of measurement | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Pre-video | 61.79 | 29.17 |

| Negative | Post-video | 63.05 | 29.75 |

| Negative | Total | 62.42 | 29.46 |

| Positive | Pre-video | 60.98 | 31.38 |

| Positive | Post-video | 67.33 | 30.20 |

| Positive | Total | 64.16 | 30.79 |

| No-portrayal | Pre-video | 66.63 | 28.64 |

| No-portrayal | Post-video | 67.17 | 28.95 |

| No-portrayal | Total | 66.90 | 28.80 |

| Total | Pre-video | 63.21 | 29.61 |

| Total | Post-video | 65.88 | 29.46 |

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation of feeling thermometer ratings (pre-video and post-video) assessing attitudes towards transgender people in all three types of portrayal – negative, positive and no-portrayal. As presented in the table, as well as in Figure 1, when comparing the mean rating of attitudes towards trans people before the priming/control videos, participants in the no-portrayal condition had more positive attitudes towards them ( M = 66.63, SD = 28.64) than participants in the negative ( M = 61.79, SD = 29.17) and the positive ( M = 60.98, SD = 31.38) conditions. However, after watching the videos, participants viewing a positive portrayal reported the most positive attitudes towards trans people ( M = 67.33, SD = 30.20), followed by no-portrayal ( M = 67.17, SD = 28.95) and negative portrayal ( M = 63.05, SD = 29.75). The largest increase in positive attitudes occurred after viewing the positive portrayal, and although a slight increase in attitudes also occurred after watching a negative portrayal, the attitudes were still the most negative in the negative portrayal group, compared to the other portrayals. Viewing a no-portrayal video affected participants’ attitude changes the least.

Interaction effect and overall findings

A 3x2 mixed-design ANOVA found a significant main effect of point in time of measurement on attitudes towards transgender people, measured by the feeling thermometer, F (1, 129) = 6.90, p = .01. This suggest that viewing priming/control videos had an influence on participants’ attitudes, with the rating of the feeling thermometer being higher post-video. The main effect of the type of portrayal on attitudes towards transgender people was non-significant, F (2, 129) = .27, p > .05, meaning that seeing different types of portrayal videos did not solely influence participants’ attitudes. Nevertheless, there was a significant interaction effect of time of measurement and the type of portrayal on attitudes towards transgender people, F (2, 129) = 3.11, p < .05. Overall, participants’ attitudes towards transgender people were the most positive after viewing the positive portrayal video, and the most negative after viewing the negative portrayal video, with the largest increase in positive attitudes occurring in the positive portrayal condition.

Discussion

The study hypothesised that there is a significant interaction effect between the type of portrayal and the point in time of measurement on attitudes towards transgender people, with the most positive attitudes occurring after viewing a positive portrayal video, and the most negative after viewing a negative portrayal video. The 3x2 mixed-design ANOVA found that this was indeed the case, and the experimental hypothesis was accepted.

Link to existing research

Gillig et al. (2018), as well as Taracuk and Koch (2021), found that exposure to positive trans storylines in Hollywood TV shows increased positive viewer attitudes towards transgender people. This is in line with the current study’s findings. Moreover, Taracuk and Koch (2021) found a significant interaction effect between the type of intervention (positive vs no-portrayal) and time of measurement (pre-intervention vs post-intervention) on attitudes towards transgender people. This is similar to the interaction effect found in the current study, with the difference being that the current study also included a negative type of portrayal/intervention.

Although Jones et al. (2018) found that exposure to trans storylines on television led to more positive attitudes towards transgender people, their findings also suggested that the type of portrayal viewers watched did not have an effect of their attitudes. This was partially supported by the current study, which found no significant main effect of the type of portrayal and attitudes towards transgender people. However, viewing positive portrayals of a trans character reduced negative attitudes towards trans people, more than viewing a negative portrayal and no-portrayal videos. Therefore, the relevance of the type of portrayal being viewed should not be dismissed entirely.

Two main differences between the current and previous research is the different methodology and different length of material. Previous studies used different scales, while the current one used a feeling thermometer, which allowed us to minimise participants’ response bias by the inclusion of a number of distractor items. Previous studies also used full episodes from TV series or programs, whereas the current study used short video clips. This makes the current research the first to find that a video as short as 5.23 minutes could influence participants’ attitudes towards trans people by reducing negative attitudes.

The current study was mostly in line with the existing research, finding that viewing positive portrayals of trans people increases positive attitudes towards them. However, a current study also addressed the gap in the literature by including a negative portrayal of transgender people and finding that such a portrayal, presented in a short video, did not have a negative influence on the viewer attitudes.

Implications

Taking into consideration the current study’s finding of Hollywood fiction influencing viewer attitudes towards transgender people, as well as the rate of violence towards transgender people explored in the introduction, people working within the television and film industry should be aware of the impact on viewers of portraying trans characters in fiction. Hollywood’s history of portraying trans characters could be classified as problematic, and filmmakers now have a chance to contribute to a positive change within the industry by portraying transgender characters in a positive way.

The current study provided evidence of short clips being sufficient to reduce negative attitudes towards transgender people, and future work could investigate both educational and therapeutic interventions, using this method. If findings are replicated with younger participants, or individuals with destructively negative attitudes towards trans people, this opens up a number of applications designed to develop positive attitudes towards this group, and to reduce negative ones.

Limitations

The main limitation of the current study is that all trans-binary participants and the majority of the trans non-binary participants were randomly allocated to the no-portrayal condition. Potentially, this could have been a reason for the attitudes towards transgender people being the most positive pre-video for the no-portrayal, and it could have led to the interaction effect not having a higher significance level ( p = .048). Another reason could have been an inappropriate choice of a negative portrayal video. Although the previous literature identified Ace Ventura: Pet Detective as a classic negative portrayal of a transgender storyline (de Castro, 2017), the film could now be too outdated for this study conducted in 2022. Additionally, there is a possibility that using only a short video from the film did not show the full context of how the trans female character was negatively portrayed as a criminal, and participants could therefore feel sympathy towards her. This may be why there was a slight increase in positive attitudes after watching the negative portrayal video.

Future directions

There is a gap in the literature when it comes to using a negative portrayal video to influence participant attitudes towards transgender people, and the video used in the current study may be outdated. Although no recent popular Hollywood films or TV series were identified in previous literature as portraying trans characters in a negative way, these are not the only forms of Hollywood entertainment media. There has been a trend amongst popular comedians, notably Dave Chappelle and Ricky Gervais, to include humour perceived as transphobic in their Netflix stand-up specials (Murphy, 2022). This has opened a general discussion on whether their stand-up comedy was simply entertainment, or whether these jokes may contribute to the discrimination and violence that trans people face. Therefore, future studies could consider using a clip from stand-up shows including transphobic humour, and a clip from a trans-positive stand-up, in order to investigate whether exposure to stand-up comedy could influence participant attitudes towards transgender people.

Conclusion

The current study found a significant interaction effect of the type of portrayal and the point in time of measurement on attitudes towards transgender people, which revealed that watching short videos from Hollywood fiction was sufficient to increase positive viewer attitudes towards transgender people. Particularly watching a video that positively portrays a transgender character reduced negative attitudes towards trans people more than viewing a negative portrayal and no-portrayal videos. Future plans are to replicate the current study with the use of stand-up comedy videos, due to recent debates on transphobic comedy perpetuating the discrimination of transgender people. It is certainly important for researchers to continue investigating the influence of media on attitudes towards transgender people, due to the sadly high level of violence and discrimination that continues to be aimed at transgender people.

References

Barnett, B. S., Nesbit, A. E. and Sorrentino, R. M. (2018). The transgender bathroom debate at the intersection of politics, law, ethics, and science. The journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law , 46(2), 232-241. https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.003761-18

de Castro, J. J. B. (2017). Psycho killers, circus freaks, ordinary people: A brief history of the representation of transgender identities on American TV series. Oceánide , 1 (9), 5-20. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6236610

FORGE (2015). Transgender sexual violence survivors: A self help guide to healing and understanding. https://forge-forward.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/self-help-guide-to-healing-2015-FINAL.pdf

Gillig, T. K., Rosenthal, E. L., Murphy, S. T. and Folb, K. L. (2018). More than a media moment: The influence of televised storylines on viewers’ attitudes toward transgender people and policies. Sex Roles , 78(7), 515-527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0816-1

GLAAD (2012). Victims or villains: Examining ten years of transgender images on television. https://www.glaad.org/publications/victims-or-villains-examining-ten-years-transgender-images-television.

Government Equalities Committee (2018). Reform of the gender recognition act: Government consultation. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/reform-of-the-gender-recognition-act-2004

Human Rights Campaign (2021). Fatal Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2021. https://www.hrc.org/resources/fatal-violence-against-the-transgender-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2021

Jones, P. E., Brewer, P. R., Young, D. G., Lambe, J. L. and Hoffman, L. H. (2018). Explaining public opinion toward transgender people, rights, and candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly , 82(2), 252-278. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy009

Koch-Rein, A., Haschemi Yekani, E. and Verlinden, J. J. (2020). Representing trans: visibility and its discontents. European Journal of English Studies , 24(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2020.1730040

Leighton, K., Kardong-Edgren, S., Schneidereith, T. and Foisy-Doll, C. (2021). Using social media and snowball sampling as an alternative recruitment strategy for research. Clinical Simulation in Nursing , 55, 37-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.03.006

Murphy, C. (2022, May 26). The Difference Between Dave Chappelle and Ricky Gervais. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2022/05/the-difference-between-dave-chappelle-and-ricky-gervais

Neff, C. (2015). The Jaws Effect: How movie narratives are used to influence policy responses to shark bites in Western Australia. Australian journal of political science , 50(1), 114-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2014.989385

Norton, A. T. and Herek, G. M. (2013). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward transgender people: Findings from a national probability sample of US adults. Sex roles , 68(11-12), 738-753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0110-6

Reitz, N. (2017). The representation of trans women in film and television. Cinesthesia , 7(1), 1-7. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1125&context=cine

Taracuk, M. D. and Koch, J. M. (2021). Use of a media intervention to increase positive attitudes toward transgender and gender diverse individuals. International Journal of Transgender Health , 42(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1878479

About the authors:

Martyna Zuzanna Lipińska is a postgraduate student in Creative Arts and Mental Health at Queen Mary University of London.

Dr Rosemary Stock is interim Head of Psychological Sciences at the School of Human and Social Sciences, University of West London.