Introduction

A recent literature review by the Centre for Ageing Better (2020) concluded that ageism, the systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against older people, was ‘still rife’ in the UK, including in its media. Considering the country’s increasingly ageing society, with the share of those aged 65 years or over now standing at almost 19% of the UK’s total population (Eurostat, 2021), this conclusion is a cause for concern. Although ageist portrayals may provide comfort for younger people by maximising group differences and reducing the anxiety associated with growing old, they deny the individuality of ageing and ignore the extreme heterogeneity which exists within the older population. The most salient feature of ageism is not so much its depiction of ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ images associated with old age, but far more its limiting effect. ‘What makes a portrayal racist, sexist, or ageist is the repetition of the same types of behaviors over and over again to the point of limiting, denying, or excluding other potentials. A full range of human potentials is denied the individual; constricted roles become the norm’ (Ansello, 1977, p.255).

In a previous paper, we considered how older members of British society were portrayed in market communication and how these schematic portrayals might still reflect ageist public views which focus, amongst other things, on gendered ageing (Olsen & Scott, 2021). With the UK’s population gradually growing older, its population is also becoming increasingly ethnically diverse. It is estimated that currently, around 8% of the nation’s older population belongs to minority ethnic groups (Age UK, 2019). Socio-cultural artefacts, such as advertising, have slowly started to reflect a more multicultural modern Britain (Lloyds Banking Group, 2018). However, research by the Advertising Association (2014) has found that advertising is falling short of portraying a realistic image of Britain’s multicultural population, crafting distinctively different stories for white characters compared to those from minority ethnic backgrounds.

This short paper presents insight into the commonalities and differences between promotional narratives told with older adults from different ethnic backgrounds in current British TV advertising. The objective is to investigate the ethno-gerontological hypothesis of double jeopardy (Torres, 2015), according to which older minority ethnic groups are at a double disadvantage, firstly due to their age and secondly due to their ethnicity. Intersectionality theory picks up on this, by acknowledging that the overlap of various social identities, such as a person’s age, race, gender, sexuality and class may contribute to the specific type of systemic oppression and discrimination experienced by an individual (Bowleg, 2012). In the context of market communication, this topic is of interest, as consumers expect brands to represent different parts of society positively yet accurately, and consumers view brands that accomplish this in a more favourable light (Lloyds Banking Group, 2015).

Our research is further framed by Vitality Theory (King Smith, Ehala & Giles, 2017), according to which the standing of any social group within a society is reflected by the media and, thus, can be determined through the examination of, for example, advertising. Vitality theory is based on the grouping of individuals via socio-demographic variables, such as their proportion within a population, geographical distribution, political awareness and social status. Behind this lies the assumption that groups of greater number and social importance are considered to have greater ‘vitality’, and thus continue their survival as groups, and the specific group features are propagated. A group that possesses more vitality will receive much greater support and representation in society as a whole, including in the media. Therefore, by looking at how groups are portrayed within media content, one can gain insight into the social standing and the perception of these people within a society.

For this study, we analysed commercials during British prime-time television over a period of two consecutive weeks in September 2020. All commercials aired on ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 during the investigation period were included in the analysis, resulting in a sample size of 6,228 adverts, featuring a total of 367 occurrences of characters over the age of 65 years (for details of our sample selection and coding process, see Olsen & Scott, 2021). In line with previous research into diversity, equity and inclusion in media content, our study considered both physical characteristics such as skin colour, usually associated with the social construct of race, and cultural expressions and identifiers such as clothing, in order to assign a character’s ethnicity. Categories of ethnic groups were informed by those suggested by the Office for National Statistics. The investigation comprised both media content and narrative analysis.

Findings and discussion

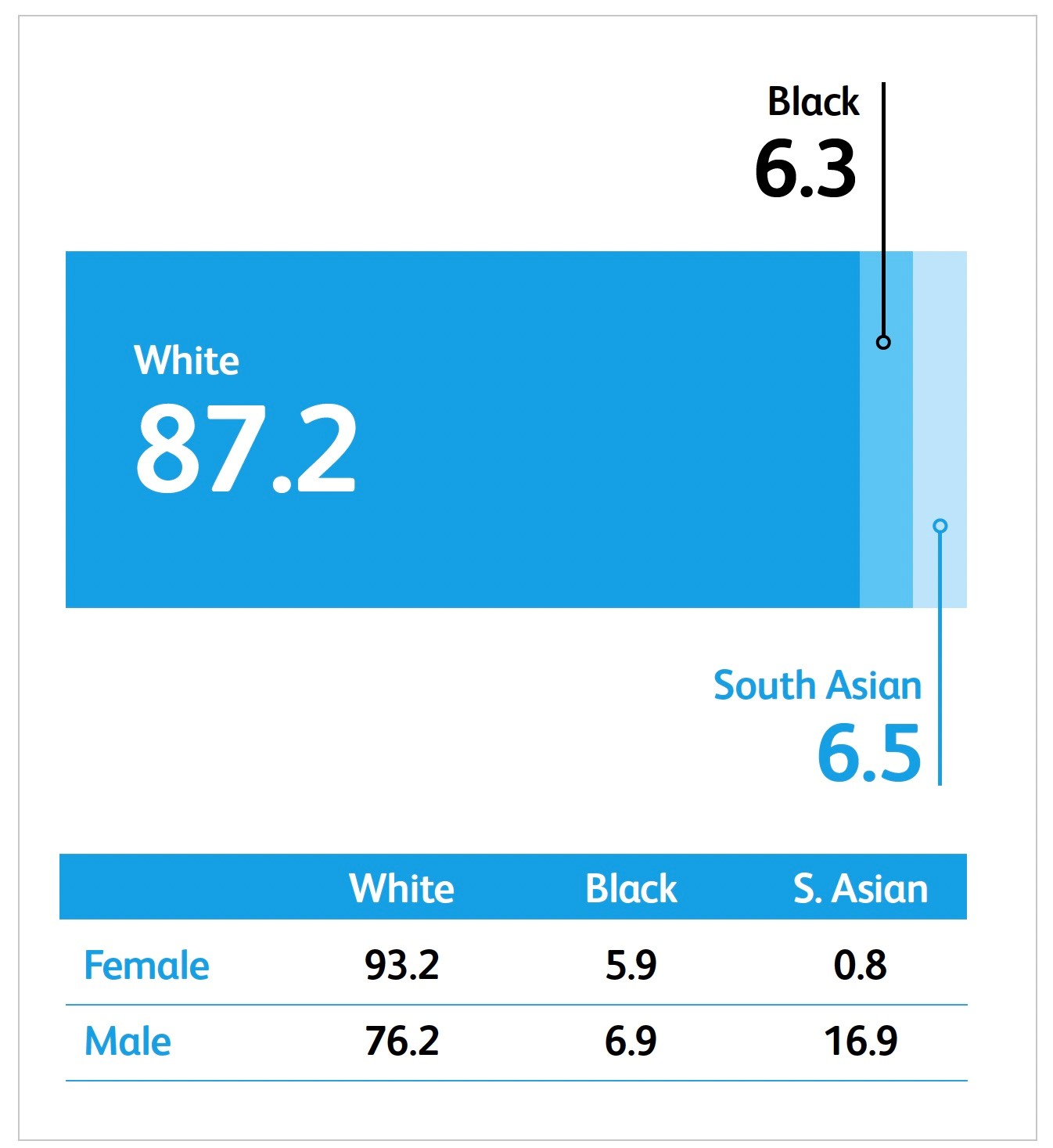

Roughly every tenth media character aged 65 years or over depicted in contemporary British TV advertising belonged to a minority ethnic group, which is higher than recorded in the population as a whole. However, minority ethnic representations were invariably limited to older Black and South Asian adults (Figure 1), and thus far from inclusive of the full spectrum of the UK’s ethnic composition.

Figure 1: Distribution of ethnicities in the sample overall and according to sex

A conspicuous gender gap was also noted. The sample featured a pronounced female skew, with almost two-thirds of all older characters being women. Yet, commercials featuring older men from minority ethnic backgrounds, in particular of South Asian descent, occurred significantly more often during the investigation period, compared to those featuring older minority ethnic women. As frequent exposure contributes to the overall impression that audiences gain about older adults in the long term (Chen, 2015), this might result in a misconception that ethnic diversity in the UK is predominantly male. Contemporary British TV advertising still shies away from regularly featuring older women of colour. This aligns with previous findings for other forms of media, according to which minority ethnic women are often rendered invisible (Mohr & Purdie-Vaughns, 2015).

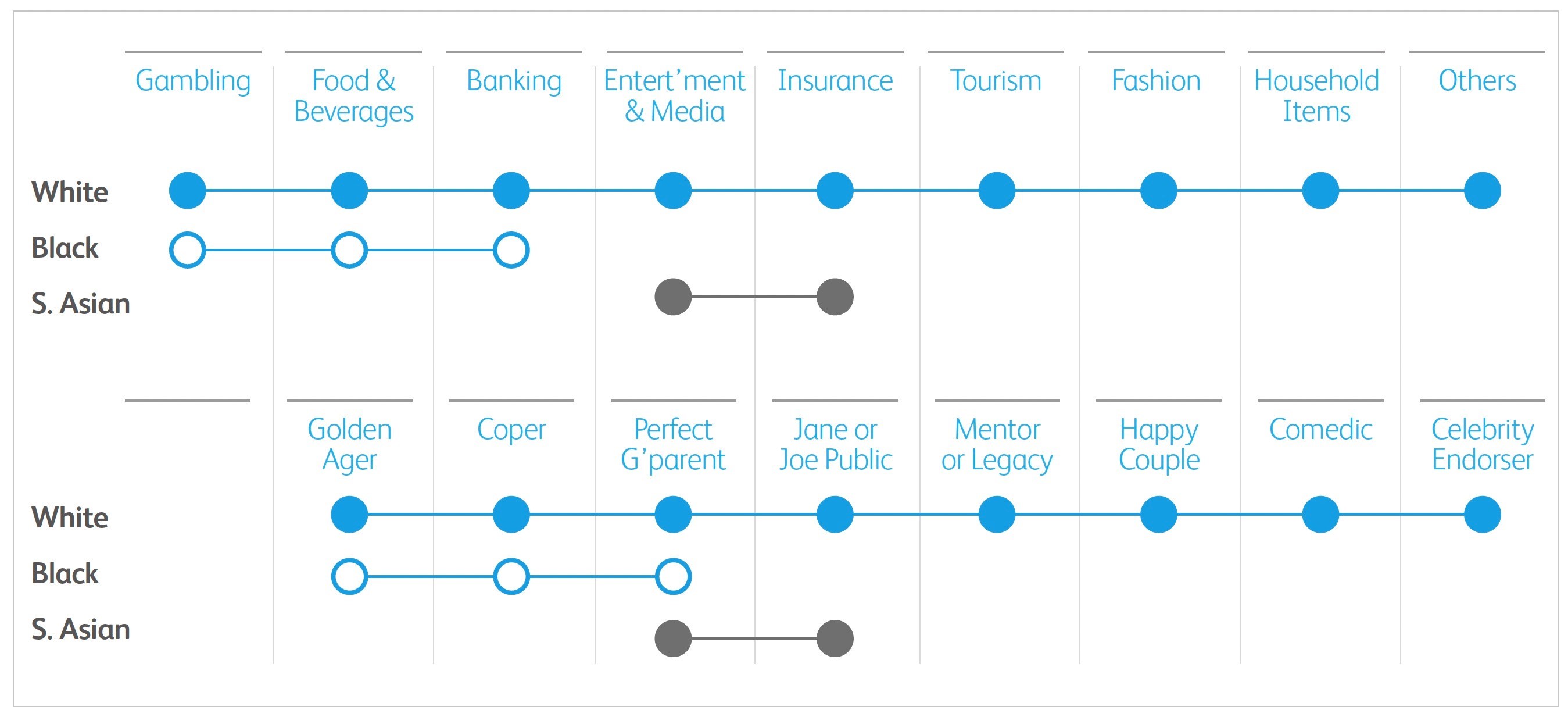

Looking at the promotional narratives—which were considered by analysing the products and services as the central topic of each advertisement, as well as the use of schematic character types—both older Black and South Asian adults were subject to significant limitations in terms of versatility. For them, a narrow number of different narratives were used (Figure 2). Older Black characters featured in commercials for only three different product groups; namely, gambling (8.7%), banking services (13%), and foodstuffs (78.3%). Older South Asian characters were even more severely restricted, appearing only in commercials for entertainment (8.3%) and insurance services (91.7%). The limitations for ethnic minority characters in advertising in Britain have been documented previously, but without reference to age (Mogaji, 2015). However, these appear to be even more pronounced in older characters of colour.

Figure 2: Distribution of ethnicities according to product categories and character types

A similarly limited pattern emerged for the use of character types. Older Black adults were only associated with three distinct character roles in the stories told by advertisers. They were portrayed as: (i) ‘Golden Agers’—older people who are youthful and full of zest, actively enjoying their advanced years. The long-running campaign ‘Sapeurs’, for the Irish stout Guinness , is an example of this. Two older Black men are shown dancing in a bar in front of a cheering crowd, celebrating their heritage rooted in Congolese culture. Liveliness and enjoyment are at the centre of this campaign for the alcoholic beverage. (ii) ‘Perfect Grandparents’—older people who are shown with their grandchildren, sometimes surrounded by several generations. In the commercial ‘Family’, for British cider maker Thatchers , the camera cuts to an older Black woman being lifted off the ground in a loving embrace by her grandson. Seemingly surprised by his visit, the female protagonist is overcome with joy and content. (iii) ‘Copers’—older people facing a problem, such as compromised health, but who are coping with it thanks to the product or service being advertised. The People’s Postcode Lottery’s commercial, ‘Goldies’, features a jolly multicultural group of older men and women, including several older Black adults, participating in singing therapy to combat social isolation via community singalongs.

Once again, older South Asian adults faced greater limitations, being only ever cast in the slice-of-life role of ‘Jane or Joe Public’, or as the ‘Perfect Grandparent’. Examples for these included commercials by the British Broadcasting Corporation ( BBC ) and international health insurer Bupa . The BBC’s image campaign features several people of different ethnicities and ages, including an older South Asian woman who is seen sitting comfortably on her sofa at home, smiling at the TV, seemingly content with her chosen entertainment. She represents one of many people in Britain who have sought comfort in television during the challenges of 2020. Bupa’s campaign ‘Back to normal’ broaches the issue of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, featuring emotional cut-scenes of an older South Asian man at the front door of his home, embracing a member of his family in what appears to be an emotional reunion after an extended period apart, due to the pandemic.

Throughout the investigation period, both Black and South Asian characters aged 65 years or older were significantly more likely to be featured in major roles compared to older White characters. Yet, older White adults covered a considerably broader variety of both product categories and character types (for a complete typology of older characters observed in contemporary British advertising, see Olsen & Scott, 2021), resulting in the pigeonholing of older Black and South Asian adults, and leading to restricted opportunities to showcase a ‘full range of human potentials’ (Ansello, 1977, p.255) as part of contemporary promotional narratives in Britain. Finally, storylines featuring affluent older characters were exclusively reserved for White British adults.

Notwithstanding the somewhat limited opportunities afforded to older Black and South Asian characters, the examples mentioned in this article already indicate that this did not lead to exclusively negative promotional narratives. In fact, older Black adults were most often featured in positively connoted commercials, which might be explained by their frequent occurrence in advertisements for food and beverage products that regularly revolved around celebratory events and happy family gatherings. Social interactions with friends and acquaintances, as part of the promotional narratives, were three times as common in older Black and South Asian characters compared to older White characters, denoting distinct interpersonal ties beyond one’s close family.

Conclusion

With Britain’s ageing population growing increasingly diverse, this study contributes useful, original insights into the on-going discussion of media representations at the intersection of age and ethnicity. Media images influence people’s perception of reality and reveal and/or influence what is considered important within society. Based on our findings, it seems that double jeopardy is very much prevalent in contemporary British advertising, with the breadth of representation of older adults from minority ethnic groups within promotional narratives far from reflecting the full spectrum of the UK’s true ethnic composition. The underrepresentation of older women of colour might even suggest the existence of triple jeopardy, with age, ethnicity and sex potentially disadvantaging the vitality of this social group. The omission of certain social groups inevitably impacts the familiarity and awareness of affairs, accomplishments and needs of these groups in the broader public, thus weakening their social standing.

Our findings only partially support the claim that advertising in the UK crafts distinctively different stories for characters from minority ethnic backgrounds (Advertising Association, 2014). In 2020, different stories primarily translated into limited promotional narratives for older Black and South Asian characters compared to older White characters, rather than alternative storylines. Even in adverts for products and services that were exclusively promoted by older White adults, the schematic character types employed as part of the promotional narratives were similar to those used for minority ethnic characters in other advertising. Nevertheless, whilst ageism in the sense of denying the full range of potential was observed for all older characters irrespective of their ethnic background, this appeared to affect older Black and South Asian characters more than older White characters. Brands should thus strive towards further age and ethnic diversity, equity and inclusion in their promotional narratives.

References

Advertising Association (2014) The Whole Picture: How advertising portrays a diverse Britain. Retrieved from https://adassoc.org.uk/?download_resource=https://adassoc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/p222-15108-the-whole-picture-how-advertising-portrays-a-diverse-britain-1.pdf

Age UK (2019) Later Life in the United Kingdom 2019. Retrieved from https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/later_life_uk_factsheet.pdf

Ansello, E. (1977) Age and ageism in children’s first literature. Educational Gerontology , 2(3): 255-274

Bowleg, L. (2012) The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health , 102(7): 1267-1273

Centre for Ageing Better (2020) Exploring representations of old age and ageing. Retrieved from https://www.ageing-better.org.uk/publications/doddery-dear-examining-age-related-stereotypes

Chen, C.-H. (2015) Advertising Representations of Older People in the United Kingdom and Taiwan: A Comparative Analysis. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development , 80(2): 140-183

Eurostat (2021) Population structure and ageing. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00010/settings_1/table?lang=en

King Smith, B., Ehala, M. & Giles, H. (2017) Vitality Theory. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Communication , edited by J.F. Nussbaum, 1-22. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lloyds Banking Group (2015) Reflecting Modern Britain? A study into inclusion and diversity in advertising . London: Lloyds Banking Group.

Lloyds Banking Group (2018) Ethnicity in Advertising: Reflecting modern Britain in 2018 . London: Lloyds Banking Group.

Mohr, R.I. & Purdie-Vaughns, V. (2015) Diversity within Women of Color: Why Experiences Change Felt Stigma. Sex Roles , 73: 391-398

Mogaji, E. (2015) Reflecting a diversified country: a content analysis of newspaper advertisements in Great Britain. Marketing Intelligence & Planning , 33(6): 908-926

Olsen, D.A. & Scott, C. (2021) Golden Years, Wise Mentors and Old Fools: An Updated Typology of Older Characters in British TV Advertising. Journal of Aging and Social Change , 11(2): 83-94

Torres, S. (2015) Ethnicity, culture and migration. In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Gerontology , edited by J. Twigg & W. Martin, chapter 35. Oxon: Routledge.

About the authors

Dr Dennis A. Olsen is a Senior Lecturer in Advertising and Branding in the London School of Film, Media and Design at the University of West London.

Charlotte Scott was a Research Assistant at the London School of Film, Media and Design.